Sabzbag August-September 2020 Newsletter: Protein 101

|

|

|

|

Generating click-bait is easy, but changing our habits is costly - at least mentally and emotionally, if not financially. In the last issue we shared our information compass - a tool that makes us more adept at navigating the marketing heavy, information light celebrity and scientific clickbait land. In this and the next few issues, our team of data scientists and domain experts will dive deep into the literature to draw a simple and information-rich map of the nutrition landscape as it relates to protein. The punchline is that most of us, especially in the developed world, are getting enough protein and we do not need to obsess over it.

|

|

|

|

|

An announcement: We hope this makes up for the vacation in July. We also wanted to share a logistical shift- we are going to work harder to produce more in-depth research - but have to shift the newsletter frequency to bi-monthly. Stay tuned for the newer Sabzbag app as well as summary videos!

On a more light-hearted note, in the recipe comics we bring you Pav Bhaji - a delicious street food from Mumbai born as a result of the US Civil war.

We started our work on nutrition and health with two simple goals:

- Map out expert consensus: we will report what nutrition and health experts agree strongly on.

- Suggest simple, fun and low-cost steps towards that expert consensus, that are common sense driven and conservative. Conservatism or humility is only appropriate since all of us - even experts- have limited knowledge about our amazing human body.

Accomplishing #1 and #2 helps us with our common mission to achieve the "biggest health bang for our effort buck" while avoiding the hype.

The Great Protein Fiasco - a lesson in scientific humility and lobbying power.

In this issue we also discuss how nutritional science overestimated the protein requirement in the past, and some of the resulting high protein interventions were harmful - for instance, one protein intervention damaged babies instead of helping them. The presence of commercial interests - the US dairy industry had a lot of skim milk to sell - seems to have compounded the human mistakes that are a normal part of the scientific process. Thus whatever the experts say, we must continue to use common sense.

Reader questions on protein are at the end

Our readers are mighty curious about protein so we dug deep and tried our best to answer questions like

- Should older people eat more protein to avoid Sacropenia (age-related muscle loss)?

- Would maximizing lean meat in our diet be a good idea?

- Is it bad to eat "too much" protein?

- Are there links between protein and longevity?

We understand that not everyone is interested in each question so please skim and read whatever is relevant!

Fact Check Sabzbag: All Our References Are Here

We are also making our research process transparent to make it replicable and help ourselves improve. You can check out the link above to all the materials used. |

|

|

|

|

Protein 101

We start on our protein journey with two simple questions: what is protein and how much of it do we need? This knowledge is foundational to grapple with deeper questions forthcoming in the subsequent issues:

- Links between animal protein and the diseases of the rich

- Plant protein and the diseases of the poor

- Protein's role in athletic performance.

A protein is a large macromolecule (thousands of atoms chained together) made up of amino acids that functions as a cell's "building block." Proteins perform many functions within our body - in fact, they make up almost every part of our body - our muscles, bones, skin, hair and nails, the enzymes that power chemical reactions inside us, the hemoglobin that carries the oxygen in our blood, and even help us digest our food. Apparently, us humans have around 2 to 4 million protein molecules in each cell!

There are twenty plus basic building blocks called amino acids and while our body can make some of them, about nine of them (histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine) cannot be synthesized inside our body and must come from food. These are called the essential amino acids. Both plant and animal based sources can be used to obtain these essential amino acids - which we will tackle in more detail subsequently, our focus in this issue is just on the basic information.

|

|

|

|

|

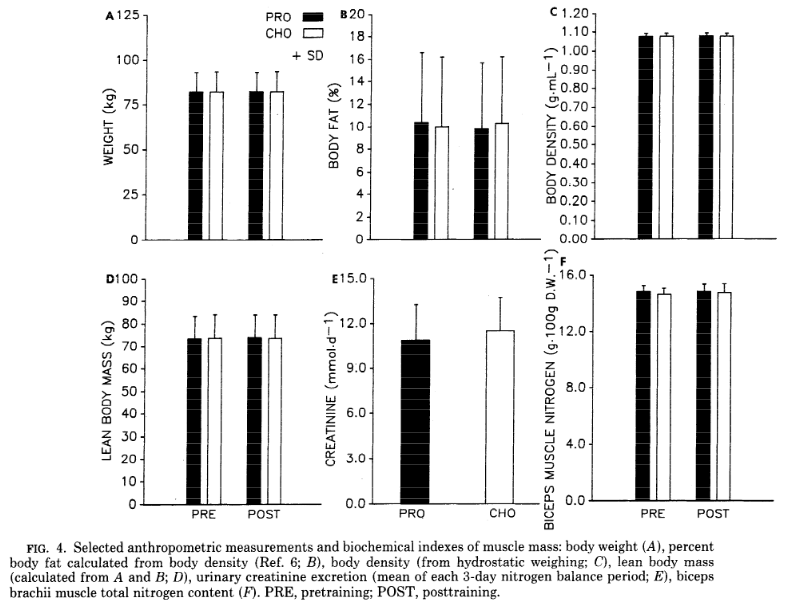

Figure 1 (top right) shows the kind of schematic diagrams scientists have to use to estimate the protein requirements. From page 27, Figure 3 of Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition. Issues by the WHO (World Health Organization). This is tough and complex - even for scientists!

|

|

Figure 2 (bottom right) shows that we can easily meet the safe daily protein requirements of 50-60 grams for a 68 Kg (150 pound) person with 3 cooked cups of lentils (~ 600g) even if they eat NOTHING else. Of course we can use animal protein too and that will have even more protein per 100 g (typically 20-30 g).

|

|

|

Estimating human protein requirements is NOT straight forwardAs figure 1 indicates, estimating the protein requirements in humans is a complex subject given to much scholarly discussion and empirically it has to employ many complicated scientific methods such as nitrogen balance, carbon balance and indicator amino acids. At a much simplified level, one of the key ideas behind nitrogen balance is that our protein need is what our body demands to maintain its nitrogen balance and the estimation takes into account the fact that we do not utilize a 100% of the protein we eat.

Protein Requirement = metabolic protein demand / net protein utilization.

Protein requirements also vary by age, gender, activity level and there are many other factors which makes this empirical estimation a difficult problem. For example, in rapidly growing animals and young babies - animal proteins are utilized at a higher percentage and plant proteins are utilized at a lower rate. However, for human adults there was no significant difference between animal, vegetable or mixed protein sources. Section 2.3, WHO report on protein and amino acid requirements says:

"This implies that for human adults, net protein utilization values for diets of most sources are similar, but much lower than would be predicted."

|

|

|

|

|

🔎 A Study in Protein Recommendations

Sorry Sherlock but we have to do this! Thus far we have learnt two things:

1. Protein is fundamental to our health.

2. Estimating anyone's exact protein requirements is not easy.

Let us add a third and very relevant fact:

3. Our incredible body can adjust to a wide variety of protein intakes and excess protein is (typically) not a big or immediate problem for a healthy human (WHO report section 13.6 ). When we put these three facts together, we can formulate some hypothesis and then test them against real life data.

💡 HYPOTHESIS 1: The acceptable range of protein must be quite wide due to the difficulty in measuring the exact protein requirement.

🎯 TEST: Let us test this hypothesis with real-life data. Indeed the National Academy of Medicine does set a wide range for acceptable protein intake anywhere from 10% to 35% of calories each day. There are many ways to meet this wide protein intake. For example, the Sabzbag 0 junk - 1 whole grain - 2 legume or other protein rich food - 3 vegetable framework ensures we get about 15% to 25% calories from protein even when consuming only vegetarian protein. In the same framework, if we choose to include animal protein, the protein percentage can be higher. In case, we have a medical condition such as diabetes or hypertension where doctors suggest consuming a lower protein percentage - closer to 10% to 15% - to protect our kidneys we can easily achieve that too.

💡 HYPOTHESIS 2: The "safe" or suggested requirement is likely to be biased towards MORE protein than strictly necessary since protein is so important and a healthy human can consume a wide range of it.

🎯 TEST: Let us examine the WHO's protein recommendations. But first we need to define some terms and set it all up.

|

|

|

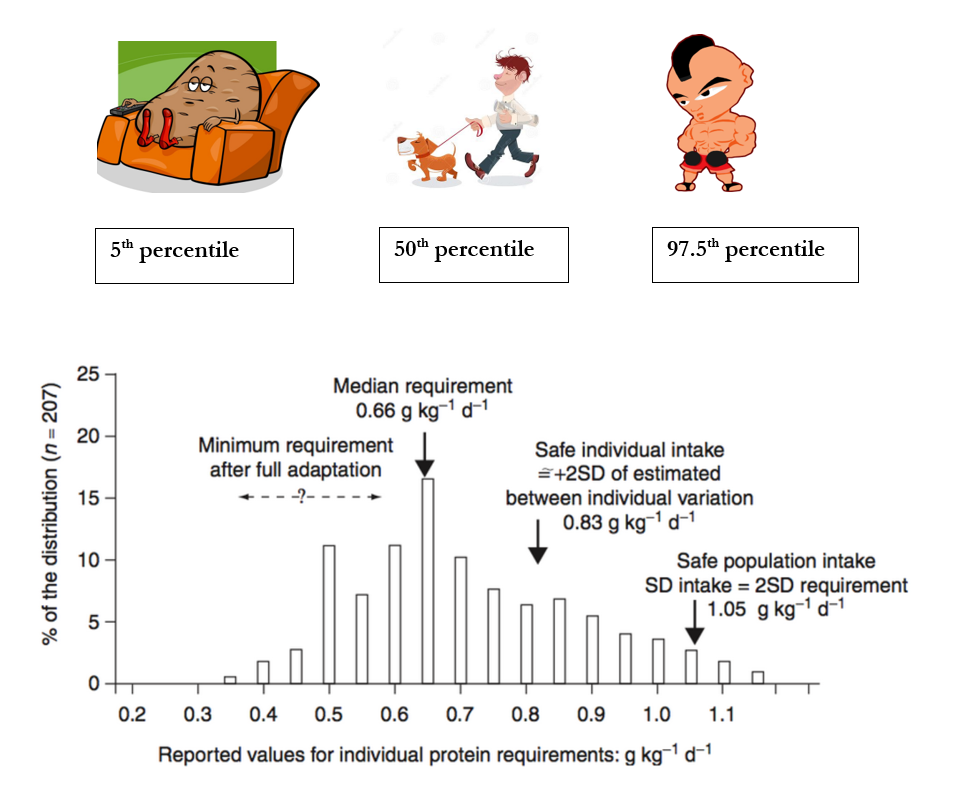

- The 100th %ile or max protein requirement: Olympic athlete AND breast feeding mom. Somehow this recent breast feeding mom is still training at the Olympic athlete level. She has THE highest protein requirement/Kg.

- The 97.5 %ile or high protein requirement: a male mixed martial arts fighter. A professional athlete training very hard but cannot biologically give birth. Thus their requirement is a bit lower.

- The 5th%ile or min protein requirement: a middle-aged couch potato who is otherwise healthy but does not move. This person does not need protein for growing like a child might and they are neither active, nor sick. Thus they have THE lowest protein requirement/Kg of body weight.

- The 50%ile or middle protein requirement: is a moderately active "normal person". This is most of us.

|

|

|

Figure 3 shows that the suggested protein requirement of 0.83 g/Kg per day is quite "safe" - the risk of a less than adequate protein is only 2.5% for an individual. The protein requirement for the person in the middle of the distribution or "median" is only 0.66 g/Kg. Thus the consumption of 1.6g/Kg of protein would be roughly 8 standard deviations away from the middle and practically speaking it is IMPOSSIBLE that this person is not eating adequate protein. Figure source. The data was obtained from a meta analysis by Rand et al. (2003) in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. The cartoons above the figure have been added by us for exposition. |

|

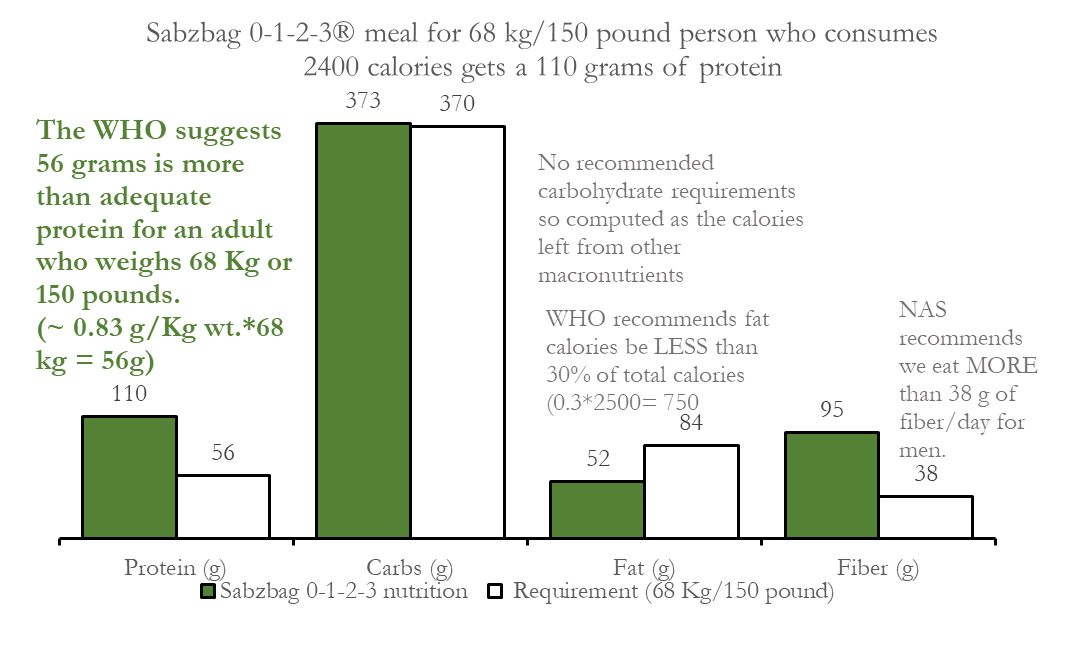

Figure 4 shows that a Sabzbag 0 junk - 1 whole grain - 2 legumes or another protein rich food - 3 vegetable type meals could easily supply 110g of protein which is MORE than the need of the 97.5th percentile at 56 g. This is higher than the median requirement by 8 standard deviations while only allowing legumes. In case we use animal proteins, our protein intake would be even higher. And of course we can tweak the plate to make this protein consumption lower also. |

|

|

👉 According to the WHO study on protein and amino acid requirements the best estimate for the 50th %ile or normal person's protein requirement is 0.66g/Kg or about 45g/day if he/she weighs about 150 pounds (68 Kg).

The requirement indicated by the meta-analysis (6) (a median requirement of 105 mg nitrogen/kg per day or 0.66 g/kg per day of protein) can be accepted as the best estimate of a population average requirement for healthy adults.

👉But the SAFE requirement the WHO suggests for this normal person is already at the 97.5 percentile requirement is about 0.83g/Kg or 56g of protein for a 150 pound (68 Kg) person. In fact, the WHO report on protein and amino acid requirements, section 7.10, page 125 states:

Although there is considerable uncertainty about the true between-individual variability, the safe level was identified as the 97.5th percentile of the population distribution of requirement, i.e. 133 mg nitrogen/kg per day, or 0.83g/kg per day protein. Thus 0.83 g/kg per day protein would be expected to meet the requirements of most (97.5%) of the healthy adult population.

In other words, the WHO wanted to be sure that we are not under- eating protein. So they issued the "safe" requirement (which accounts for population variation that is different from the individual variation) almost AS IF the entire population was a bunch of high performance athletes who train intensely every day for hours and need the appropriate protein. |

|

|

|

|

"The Great Protein Fiasco": A Historical Nutritional Mistake

Let us go back to the 1960s and the times of a "Worldwide Protein Gap"

Our conclusions above may not be easy to digest. So we thought it would be interesting to go back in history and examine what happened from 1950 to 1970 when the medical world misunderstood the genesis of a common childhood disease "Kwashiorkor" and attributed it specifically to a protein deficiency rather than a more general malnutrition.

The concept of the much-publicised world protein "gap", "crisis", or "problem" arose from the description of Kwashiorkor in Africa in the 1930s and the assumption, which has turned out to be wrong, that malnutrition in children takes this form throughout the world.

The dog that did not bark or the protein disorder that was not!

Subsequently, this disease was declared to be "the most serious and widespread nutritional disorder known to medical and nutritional science" and a concentrated effort was launched to combat it. A US based Protein Advisory Group (P.A.G.) was created to help WHO close the uncalculated but enormous protein gap. A speech in 1969 (cited in a review paper of the time, The Great Protein Fiasco) makes the case.

"It is difficult to arrive at a precise estimate of the ’ProteinGap,’ but it is certain that the deficit is so great that all provisional objectives of production of protein foods for the next decades have no chance, under any circumstances, of being surpassed." |

|

|

|

|

Sherlock Holmes considered it a clue that the dog did NOT bark and similarly if we did not find the huge protein disorder everyone said existed, we should probably take it easy when people tell us to eat more protein. |

|

Hemlines are about fashion and sometimes go up and sometimes they go down. It appears that protein recommendations follow a similar path - they were low in the 1900s, then high in the 1960s, came back down and are now inching up again! We suggest watching the fashion but do not rush to change your entire wardrobe or protein consumption based on the current trend. |

|

|

The Great Protein Fiasco Continued: US had Skim Milk to Sell

Fortunately or unfortunately, the US dairy industry had a lot of surplus and needed to sell it. A seemingly clear need and a solution. After World War 2 dry skim milk became available in the United States of America as a "fortunate by-product of a domestic surplus-disposal problem." It was clearly more satisfactory in every respect to dump it in developing countries than to have to bury it in the United States as was contemplated by the Department of Agriculture at one point.

Products that ignored local protein proved to be medically and commercially useless

Many products were made to meet this "protein gap" and most of them not only failed commercially but also failed to show significant improvement under field conditions - for instance Lysine supplementation of wheat was carried out but it failed to show any benefits.

Most of these products tended to be too expensive - Inca-parina cost nearly four times the cornmeal it replaced and would cost 1/6 the Central American's wage to feed one child - and abandoned the locally available vegetable-protein sources. There were apparently pockets of success - "product sells mainly as a pet food."

👎The terrible effect of too much protein on babies

Babies cannot digest protein as easily as an adult. In fact too much protein can be harmful to them. Tragically, as section 13.6 of the WHO report on protein tells us, we found this out at a terrible cost: in one study, 304 preterm infants were given diets containing excess protein - either 3.0–3.6 g/kg per day or 6.0–7.2 g/kg per day of cows’ milk protein. These intakes are 1.5–1.8 and 3.0–3.6 times the estimated milk protein intake of a breastfed newborn. These babies were more lethargic and had lower IQs as they grew up.

Hemlines or Protein Requirements: From LOW in 1900s to HIGH in 1960s and swinging up again!

So for protein requirements, we got back to what we thought in 1904 in the Physiological Economy in Nutrition and the protein gap was closed! Incidentally, to not produce that much protein (10 million tons per year) saved the world a lot of money - $100B in 1974!

Summing up: yet the hangover of MORE PROTEIN is GOOD lingers.

Many people in the 1960s were convinced that more protein rich food was the answer to "freedom from hunger" and some of us are still stuck there. We think it is time to stop worrying and move on! A snide English aside about a lack of theory sums it up - "Sciences not yet underpinned by theory are not much more than kitchen arts." (Sir Peter Medawarmight). |

|

|

|

|

💡 Did You Know? Extra Protein ≠ Extra Muscle

It seems surprising, but according to research - beyond a nominal amount, eating more protein does not seem to help put on extra muscle. Some athletes such as bodybuilders typically consume a lot more - about 4g/Kg or about 300 g/day for a 70 Kg athlete as compared to the suggested intake of about 1.6g/Kg bodyweight for athletes which would only amount to 120g for the same 70Kg athlete. The question is if this actually helps put on muscle?

A lot of scientists have studied the question and the WHO report section 13.6 provides an excellent summary of the answers so far. While marketing may hype up the need for extra protein, science has so far concluded that such excess amounts do not result in more muscular gains.

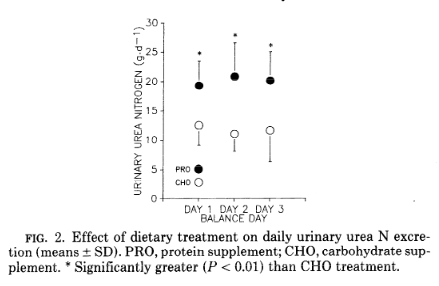

Apparently, the athlete's body adjusts to this amount and simply eliminates the excess nitrogen - the excess protein - (mostly) via the urine. The WHO report section 13.6 cites Rudman D et al.:

The study found that an increase in the protein content of a meal was followed by an increase in urea synthesis, but only up to a certain level. Above this level of intake, the rate of urea synthesis continued at the same high level for a longer period, until the excess of dietary nitrogen had been eliminated.

In short, while resistance athletes may eat more protein than the safe recommendations at ~ 1.6 -1.7 g protein/Kg body weight - which is only about 112-119 g for a 70Kg athlete - it can be easily met with food and protein supplementation does not seem necessary (National Academy of Sciences). |

|

|

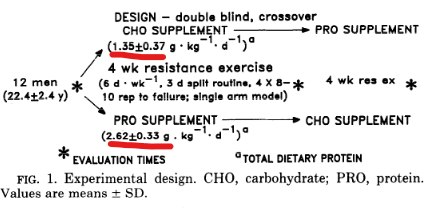

Going through ONE SPECIFIC STUDY

Let us take a specific study since we cannot go through all of them and seeing one example of how scientists do it will give us some context. Again, we want to emphasize that the overall conclusion is based on a summary of many studies or a "meta-study" as we suggested in our information compass in the last issue.

In this particular study Lemon et al.- the scientists fed young bodybuilders super high protein at 2.62g/kg per day vs. merely high protein at 1.35 g/kg per day for 1 month. Keep in mind that young bodybuilders have the highest potential for growth and hence showing some difference based on the amount of protein consumed.

Subsequently, the scientists found a BIG difference in the amount of nitrogen in the urine as we can see in the middle figure where the dark dots have twice the value of the light dots

But there was NO difference in muscle mass!

So we suggest that you save your $$$: Thus for extra muscle growth, too much protein is missing in action. So eat well, work out hard and do not worry so much about supplements.

|

|

|

Figure 5. The experiment design in Lemon et al.x A double blind counterbalanced crossover design study in which 12 healthy young males who were beginner bodybuilders - and hence subject to most potential growth - ate either high (1.35 g/kg/day) or super high amounts of (2.62 g/kg/day) protein. |

|

Figure 6. Darker circles belong to the group with The group that ate the super high amount of protein had higher nitrogen in their urine - the darker circles are higher than the lighter circles which is the group with lower protein. |

|

Figure 7. But unfortunately even these young, beginner bodybuilders showed NO difference in weight gain,body density, creatinine, or lean body mass - the black bars and the white bars are not different. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Conclusion: Relax Watson!

👉 A wide range of protein is OK and there is (virtually) NO risk of low protein

Putting it all together.

If you are in a developed country and have a "normal diet, in practical terms your risk of not getting enough protein is practically non-existent. The WHO study on protein and amino acid requirements (section 13 introduction) assures us that in reality the typical person is more at risk of excess protein rather than not having enough:

Average protein intakes of populations consuming the mixed diets of developed countries will usually be considerably in excess of recommended intakes, especially for meat-eaters.

We also chatted with our own medical expert Dr. Richa Jain, an assistant professor of Pediatric Hematology & Oncology at PGIMER, and she said " there is no such disease as an isolated deficiency of protein or isolated nutritional hypoproteinemia!"

Hypoproteinemia can exist in presence of certain diseases like gut, liver or kidney dysfunction, or it can co-exist along with diseases of undernutrition like kwashiorkor or marasmus. If a person is well nourished otherwise, and has a reasonable intake of other macronutrients, s/he can not develop isolated deficiency of proteins in today's date and age. |

|

|

|

|

After a great deal of study and investigative work |

|

|

We can safely tell everyone to CHILL OUT ABOUT PROTEIN since we are almost certainly eating MORE than the recommendation which is already MORE than what we need! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sabzbag Recipe Comics #2: Pav Bhaji |

|

|

|

Pav Bhaji is a very popular dish in Mumbai, a city on the Western Coast of India where commerce and movie stars thrive. So in this issue we bring you the movie-like story of this humble dish born during the American Civil War that eventually made its way into the hearts and tongues of people all over India!

While Pav Bhaji consists of two things - the "Pav" or the crispy bread and the "Bhaji" or the vegetables, the true essence of the dish, lies in its ingenious spice mix. This dish was traditionally made with leftover vegetables but over the years, this recipe has evolved to include a variety of vegetables. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Community Section 2.0

Hello folks we are taking a small hiatus to revamp our community and metrics section.

|

|

|

|

No, we did not eliminate our community members and replace them with bots that perform better!

Actual data and charts vs. self-delusion: For the past seven months we have been providing a glimpse into how our community deals with the challenges of being healthy, by sharing various stories and charts. We found that our eating habits were healthier during busy weekdays and worse during weekends and that we ate too much grain and junk. The charts helped us turn what were merely inconvenient and unsubstantiated suspicions into cold hard facts that demanded action.

In our very first issue we pointed out the strong correlation that existed between social interaction and the health metrics we tracked on our mobile app. The app and the data it generated for us have been valuable in helping us improve. Some of us (me included) started eating more servings of vegetables because of our monitoring and friendly competition. Anecdotal evidence is suggestive of major benefits to the individual participants in our community.

Extending the benefits to the community: After six issues, our belief in the value of community and self-monitoring has only increased. During the time we’ve consolidated valuable feedback from the community and held discussions with our medical and data experts. We are convinced that the benefits can extend from us as individuals to the community at large.

We are making a better app to achieve bigger goals: Our goal is to collect data robust enough for medical research and improve the in-app experience to make it smoother and consistent for all platforms and different user types. For us to achieve that we have to restructure our in-house app. During the rework to incorporate these upgrades the app will be offline and without fresh data the community section will be on hiatus, but stay tuned for a bigger and better community section.

|

|

|

|

|

|

EXTRA! Reader questions on protein: older people, too much protein, longevity, lean meat and cavemen...

Question: I hear that older people need more protein

Answer: Per the WHO study on protein section 7.6.2, when we are in any situation that we consume less calories - perhaps we have trauma, or are sick, or get older- then the body's requirements for protein remains the same. Thus the ratio of proteins to total food increases. In older (and immobile) people this age related loss of skeletal muscle is called Sacropenia and some studies and doctors recommend protein and other supplementation.

However, the WHO meta-study on protein notes in these situations it is much better to increase activity and hence the calorie intake rather than use supplementation. For instance, when older people started lifting weights, they gained back the lost muscle on exactly 0.8g protein/Kg of body weight.

Question: OK, so on the other side, are there dangers of eating too much protein?

Answer: For normal, healthy people a wide range is OK. It seems it is difficult to damage ourselves in an obvious or immediate way with "too much" protein. For example in section 13.3 the WHO report on protein discusses the potential of kidney stones and finds that while there is some evidence that animal protein intake can cause more kidney stones but it is not conclusive. So if you are suffering from diabetes, hypertension are at risk of kidney failure then restrict your protein, else you are OK.

Question: Do we know anything about dietary protein and longevity?

Answer: According to a recent paper in the Lancet it seems protein intake on the lower end (closer to 10% of our calories) of the spectrum is more helpful for longevity. They also suggest that we should reduce the amount of animal protein - especially red meat - while being careful to avoid frailty due to inadequate protein intake. Interestingly, the same study mentions that Okinawans - a long lived population in Japan also tend to eat about 10% protein.

Question: What if I had enough discipline to only eat lean meat? Would that not be the healthiest thing?

Answer: Apparently, no. There is a condition called rabbit starvation that happens from consuming too much lean meat without enough fat. The WHO report section 13.6 mentions anthropological studies that research the effects of eating lean meat such as rabbit meat which tends to have very low fat content. Apparently getting 45% + energy from protein "led to nausea and diarrhoea within 3 days and to death in a few weeks, a condition known as 'rabbit starvation.' ” For a more recent comparison the same article mentions two arctic explorers monitored for a year:

" Two Arctic explorers who were monitored closely for a year while consuming an exclusively meat diet. They remained fit and healthy during this period, but when one of them ate lean meat only (about 60% of energy as protein), the symptoms of “rabbit starvation” soon developed. These symptoms were rapidly reversed when the fat content of the diet was restored (15–25% of energy as protein)."

Question: Are you suggesting that my manly caveman ancestors did not have a super high protein (> 40%) diet?

Answer: No! Actually the hunter-gatherers diets seems to have protein percentages < 40% :In fact the WHO report also has some references for those who want to dig deeper into cavemen and hunter-gatherers. "Humans avoid protein intakes in excess of about 40% of dietary energy, even when consuming mainly meat."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please help us improve by taking two minutes to provide some feedback. |

| Survey |

|

|

|

|

|

|